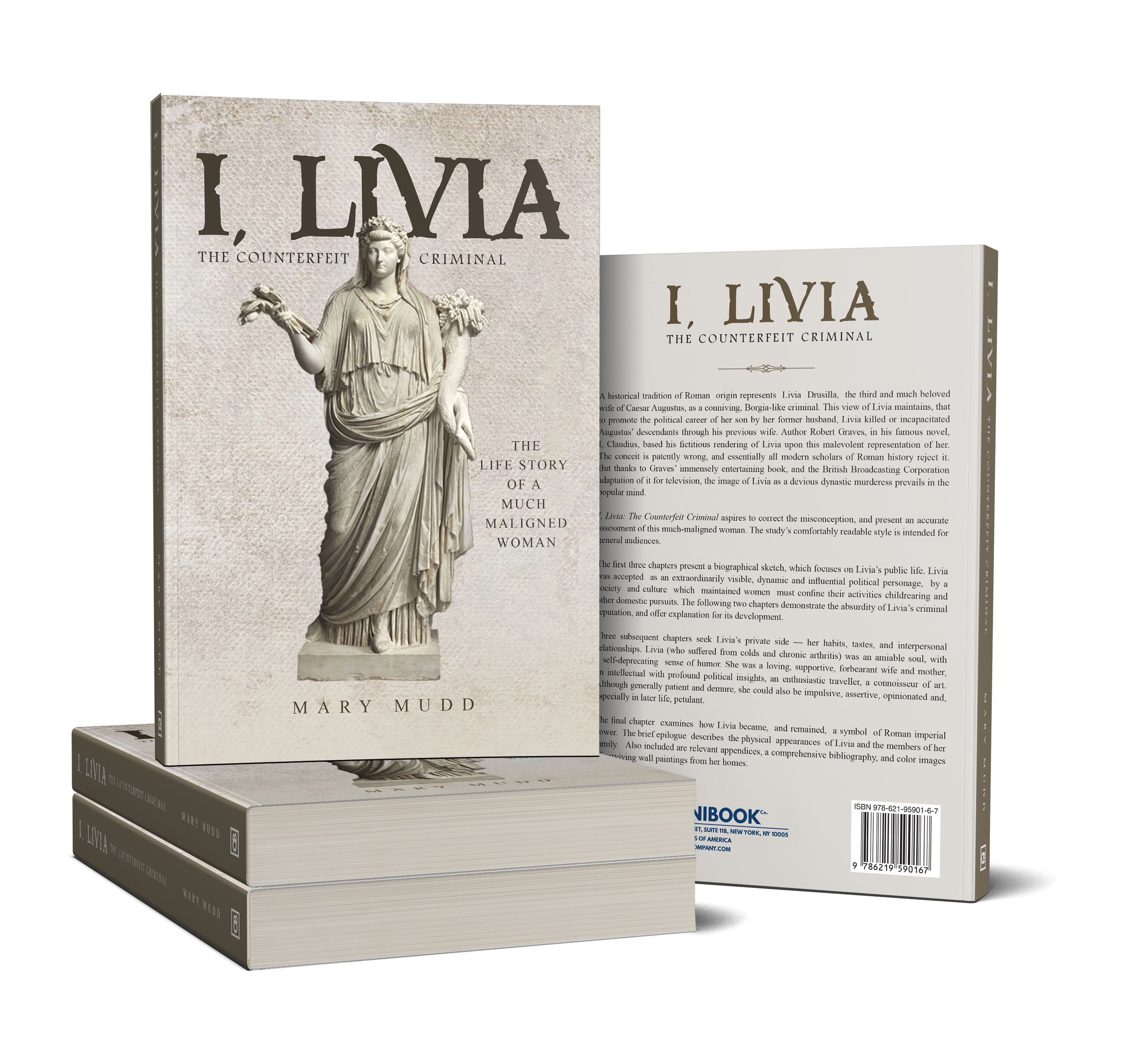

History has portrayed Livia Drusilla, the third and much beloved wife of Caesar Augustus, as a conniving, Borgia-like criminal, maintaining that Livia killed or incapacitated Augustus’ descendants through his previous wife to promote the political career of her son by a former husband. Author Robert Graves, in his novel, I, Claudius, based his fictitious rendering of Livia upon this malevolent representation. This classic book, and the British Broadcasting Corporation’s adaptation of it for television, have perpetuated the image of Livia as a devious dynastic murderess in the popular mind.

I, Livia: The Counterfeit Criminal aspires to correct the misconception, and present an accurate assessment of this much-maligned woman. The study’s comfortably readable style is intended for general audiences.

The first three chapters focus on Livia’s public life as an extraordinarily visible, dynamic and influential political personage in a society and culture which maintained that women must confine their activities childrearing and other domestic pursuits. The following two chapters demonstrate the absurdity of Livia’s criminal reputation, and offer explanation for its development.

Three subsequent chapters look at Livia’s private side – her habits, tastes, and interpersonal relationships as an amiable soul, with a self-deprecating sense of humor – a loving, supportive forbearing wife and mother – an intellectual with profound political insights – an enthusiastic traveler – a connoisseur of art. Although generally patient and demure, Livia could also be impulsive, assertive, opinionated and, especially in later life, petulant.

The final chapter examines how Livia became, and remained, a symbol of Roman imperial power. The brief epilogue describes the physical appearances of Livia and the members of her family. Appendices, a comprehensive bibliography, and color images of surviving wall paintings from Livia’s homes complement the work.

This biography has been many years in the making. Livia Drusilla has fascinated the author ever since, as a geeky, history-obsessed teenager, she has read Robert Graves’ celebrated novel I, Claudius. Was Livia the murderous, power-hungry schemer this author depicts? Was she truly ready to slay anyone who threatened to obstruct her ambitions, and clever enough to obfuscate her crimes with consummate success? Or, was she actually the loving, supportive, wife and mother her polemicists insist she only pretended to be?

Livia’s position as an empress consort naturally made her a public figure; and Augustus publicized her as an icon of his regime. More than a passive symbol, however, Livia was an active and essential participant in the operations of her husband’s administration. People accepted her as such, moreover, in a culture that traditionally restricted the responsibilities of women to homemaking and child rearing. Repulsive imputations of murder and deception tend to combine, with the cold, aloof, delineation of a government functionary, to obscure Livia’s personal, human side.

The ordinarily placid Livia could be surprisingly impulsive. For a span of at least three years, she lived in staunch loyalty to her first husband. Then she abruptly left him, while pregnant with his child, for love of the man who had driven her father to suicide and jeopardized her own safety in war. Decades later she nearly killed herself over the death of her son, and sought consolation in Greek philosophy—the ancient equivalent of psychotherapy. Livia was demure and dutiful, patient, forbearing and accommodating; but she could also be assertive, opinionated, and—especially late in her life—petulant. She was a dedicated homemaker, an accomplished intellectual, a profound political thinker, a connoisseur of art.

Gracious, generous, and amiable, she was loved and respected by her family and countrymen alike.